When direct contribution brings too much friction within your company, you might need a temporary intermediate layer as an interface. See how this evolution helps organizations maximize value flow and ROI when contributing to open source.

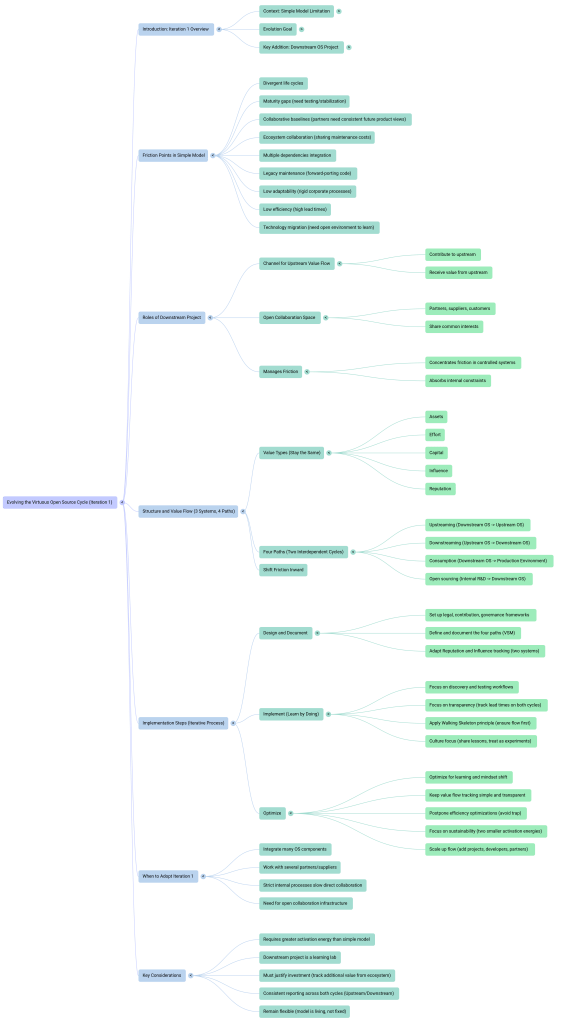

1. Introduction: Evolving the Model

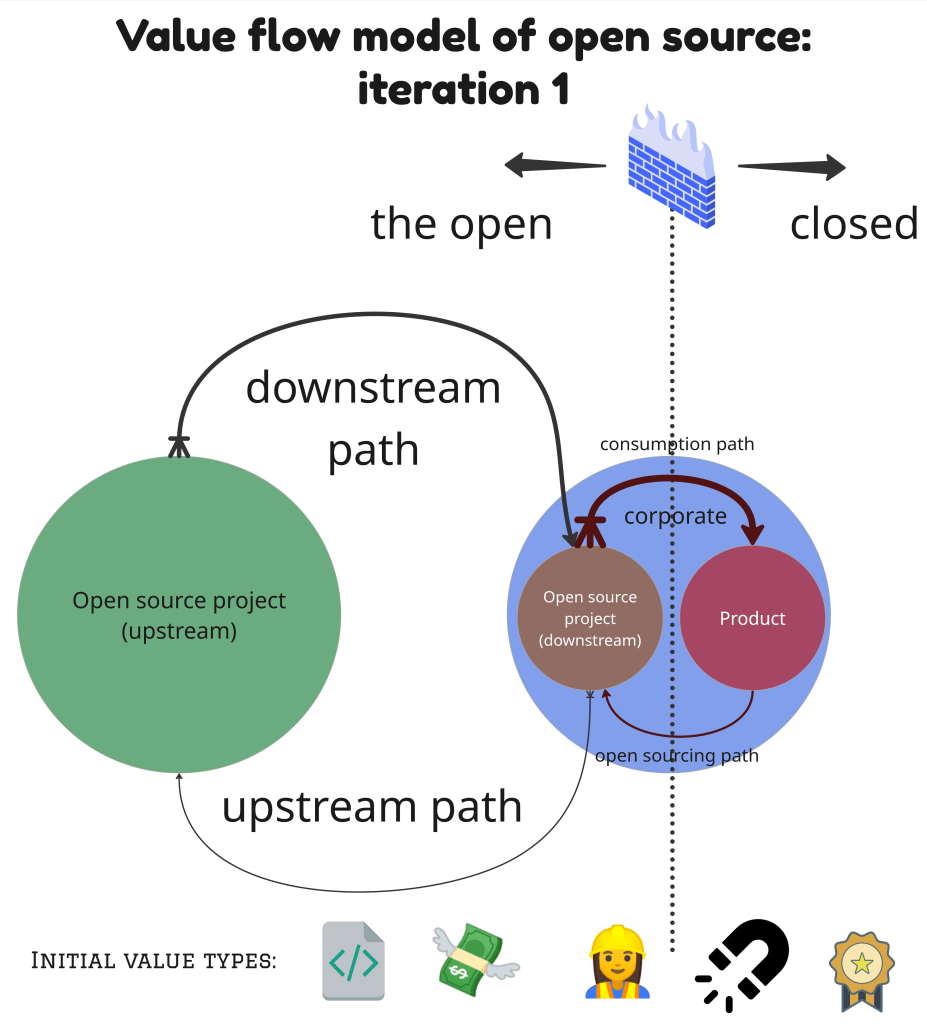

In the inaugural post of this series, “The Virtuous Open Source Cycle: Model Description“, we introduced a foundational framework for understanding how companies can contribute to open source projects while capturing amplified value in return. This model showed two environments: the open community space and the corporate internal domain. It included two core systems, two paths for value flow, and different types of value, resulting in a cycle that sustains itself once the initial activation energy is achieved. The subsequent article, “From Theory to Practice: Leveraging the Virtuous Open Source Cycle for Long-Term Success“, translated this theory into actionable strategies, emphasizing path optimization, value measurement, and common pitfalls such as the efficiency trap in communal contributions.

While the simplest iteration of the model serves as an effective starting point for many organizations, real-world complexities often necessitate evolution. This third installment explores a first iteration of the model, where I introduce an intermediate open source project, within the corporate environment, allowing companies to scale collaboration without breaking the virtuous cycle.

2. When the Simple Model Is Not Enough

In the basic model, a company consumes and contributes directly to an upstream open source project. This works well when both evolve at similar speeds, and when integration and testing can happen seamlessly. But in many real situations, the direct loop becomes hard to maintain. Common friction points include:

- Divergent life cycles: the open source project and the product evolve on different timelines, making synchronization difficult.

- Maturity gaps: code from upstream needs stabilization or testing before integration into the company’s product.

- Collaborative baselines: your current or future partners need consistent baselines of your “future product” to develop user-centric parts of the code base or hardware enablement. Sharing these “baselines” in the open allows effective collaboration.

- Ecosystem collaboration: you may want to open a collaboration space with other companies to share the cost of maintaining commodity code or to jointly mature critical code for your future product.

- Multiple dependencies: your need to integrate and customize code from several upstream open source projects before taking technical decisions and you want to do that together with your ecosystem.

- Legacy maintenance: you might partly rely on unmaintained upstream versions and need to forward-port parts of your code into newer maintained releases.

- Low Adaptability: Corporate development, delivery, and compliance processes are rigid and tailored for internal environments only. This makes a constant code flow or financial investments throughout the cycle difficult.

- Low Efficiency: Corporate development and delivery processes show high lead times or suffer from long-term constraints. This makes the upstream contribution flow difficult to sustain.

- Technology migration: you might need an open environment to learn and experiment with upstream code working in a “close enough to your corporate environment” before introducing a new technology into your product.

When one or several of these situations occur, maintaining a simple, direct open source value flow cycle might become inefficient. To fix this, creating a downstream open source project makes sense. It helps the organization preserve the value flow while concentrating most of the friction in systems they control.

In summary, if your company can already collaborate smoothly with upstream projects, there is no need to add a downstream one. But if friction makes the value flow inefficient, then this model can increase throughput across the different systems, making the overall ROI greater.

3. Iterating the simplest contribution model

This first evolution of the model, Iteration 1, adds a new element: a downstream open source project, also referred to as a corporate open source project or corporate downstream project. It is an open source project, but one that is under the company’s control.

This project works as a bridge between the company’s product and the upstream open source project. It gives the company a space to adapt, test, and integrate code before sending it upstream again. The downstream project has two main roles:

- It acts as a channel to contribute to and receive value from the upstream project.

- It becomes an open space for collaboration with partners, suppliers, or customers who share common interests.

In the new diagram, you can see this extra open node placed between the product and the upstream project. It makes the model a bit more complex, but also more flexible.

The goal of this change is not to replace the first model, but to evolve it to better fit reality while helping companies in growing the value flow, even when internal processes or dependencies create friction. As explained in the second article, success depends on keeping the whole cycle efficient, not just individual parts. This iteration helps you do that when direct collaboration with the upstream project becomes difficult.

The value types stay the same. We will refer to the most relevant at first: assets, effort, capital, influence, and reputation. They now flow through three systems instead of two. As shown in the diagram, there are two different cycles, so four paths:

- Upstreaming: contribution path from the corporate/downstream open source project to the upstream open source project

- Downstreaming: return path where the value flows from the upstream open source project to the downstream company-driven, open source project

- Consumption: return path where the value flows from the company’s open source project to the production environment, behind the firewall

- Open sourcing: The path or process where value flows from the company’s internal R&D or production environment to the open source project they control.

The diagram helps you visualize the structure of these environments, systems, paths, and assets. While each path needs its own process and has different requirements, they all must work together. The goal is to shift friction inward, where you can manage and measure it. This means external paths to the upstream project should be simple, and internal paths (around the downstream project) should absorb constraints.

If you adopt this Iteration 1 model, make sure the justification goes beyond solving internal friction. You must maximize and track the additional value generated through ecosystem collaboration that you could not achieve otherwise.

This iteration usually works best for organizations that:

- integrate many open source components,

- work with several partners or suppliers, or

- have strict internal processes that slow down direct collaboration with upstream projects.

For smaller or more agile teams, the simple model may still be a better choice. It has fewer overheads and requires less management. When evaluating the new model, it helps to look at both efficiency and learning:

- Efficiency: are code and knowledge flowing faster and with less friction? Are internal teams and external partners working better together?

- Learning: are teams gaining the experience needed to improve future collaboration with upstream projects?

The goal of this evaluation is not only to measure results, but to understand when this model makes sense and when it doesn’t.

4. Design and document the new model

Start with the basics. Set up legal, contribution, and governance frameworks. This is the first step, as noted in the first post. It enables value flow, the “plumbing” for exchange. The legal frameworks includes compliance and risks mitigation. Set them up so the friction with upstream is low. Ensure your license policy aligns with upstream, for instance, so open source licenses assigned to the code you generate within the downstream project are compatible, if not the same, that those in the upstream open source project. Again, this is not the focus of this article series.

In the previous, simpler model, the focus was on maintaining smooth value flow between your teams and the open community. In this Iteration 1, that flow becomes multi-layered, and each layer introduces potential bottlenecks. Therefore, your initial focus must be to define these paths and make them visible. Then document them, adding simple diagrams to map every milestone and every step of each one of the paths.

Adapt Reputation and Influence. In this first iteration of the model, you will track these value types in two different open source systems/environments: the upstream project and your downstream open source project. Both value types behave differently in these systems, so they will require different metrics and KPIs. Depending on many different factors, specific to your organization, tracking other value types might need adaptations too.

In summary, the goal is to design the new model for smooth, continuous flow through all four paths (two interdependent cycles).

5. Implement the model

Focus on discovery: after setting up the basic paths and frameworks, the next phase is to learn by doing. The first contributions are not only about assets and value, they are about discovery. At this stage, the goal is to understand how your model works in practice. Each contribution helps you test the rules, tools, and workflows you have designed. You will quickly see where friction appears and where the flow works well.

Focus on transparency: At this stage, the goal is to make every participant—internal or external—understand how the model works. Track all paths using Value Stream Mapping (VSM), as I suggested in the first article. Map milestones and measure lead times on both cycles. For example, track the time from a code idea to its merge, and from an upstream release to its approved landing in your repositories.

The walking skeleton principle applies here and is critical. Make sure that the value is flowing across both cycles first. You will learn the most as code and other assets flow across both paths. Once the downstream project is running and the code is flowing across both cycles, it is time to evaluate how well this new iteration of the model works.

Compared to the simple model from the first article, this version introduces complexity and costs. However, it also adds more flexibility and room for collaboration across your company’s ecosystem. Crucially, it takes pressure off your internal teams, giving them more time to adapt product development practices to open source ways of working.

Some of the key questions you need to answer at this point are:

- Does this extra layer of complexity create more value compared to its costs?

- Is it simpler now to understand how value flows so we can maximize ROI?

- How do we track value flow and report about the ROI?

Success in this phase depends less on technology and more on culture. Encourage your teams to share lessons learned. Treat early attempts and outcomes as experiments, so there are no failures. The downstream project should give you space to learn without the pressure of immediate success. Over time, this learning will become the foundation for a more efficient, scalable virtuous open source cycle.

6. Optimize the model

Here are some principles or approaches I recommend you to follow once you have the model implemented end to end.

- Optimize for learning; think of this phase as a learning one to understand if this model makes sense and when it doesn’t. This approach should help your company and ecosystem staff to adapt to the new model as a necessary step towards developing a new mindset. They should learn how to work in an open source environment while keeping alignment with corporate goals. This balance will be essential to maximize the ROI overtime.

- Keep value flow tracking simple and transparent; initially, the goal is understanding flow, not performance evaluation. You will also need to understand how collaboration in the downstream environment contributes to upstream. Dependencies between the three systems will determine the model performance to a great extent.

- Postpone efficiency optimizations; as we discussed in the second article, premature optimization might lead to the efficiency trap. You might waste time and effort perfecting the wrong things. Leave these optimizations for later.

- Once you feel that you understand how the model works and the gap with reality is manageable, begin by measuring flow efficiency. Use simple metrics such as delivery process performance metrics, backlog efficiency index… and their relation with activity and key events (upstream and downstream releases, product launches, key corporate and open source events, etc. ). Identify whether the intermediate project helps reduce friction, or if it only shifts it somewhere else. If most friction now happens in a system/environment you can control, like the downstream project, it means you can address it systematically.

- Then focus on sustainability; a model is virtuous when it sustains itself. This iterated model is formed by two different cycles, with their corresponding activation energy. They should be different from each other and smaller than the activation energy of the simplest model. But combined, they will be greater. In some cases, significantly greater. For the same upstream project, if this is not the case, there is something wrong, either in this model, or in the implementation you did of the simplest one, in my experience. Bear in mind though that each system/environment involves different activation energy. And even the same project involves different activation energy in two different points in time. Upstream projects evolve too.

- Finally, focus on efficiency optimizations while scaling up the value flow. Add a second upstream project, and a third one… Involve mode developers, additional roles, more partners, more code, more capital…

I will end the description of this iteration 1 model with three remarks:

- Remain Flexible; your paths will evolve, your downstream project will grow, your relationship with upstream will change, upstream itself will also evolve, new partners will join your ecosystem… keep learning and keep adjusting. Treat your contribution model as a living model, not a fixed one. The diagram shows the structure only. But the real model lives in your daily practice. Let that practice teach you and drive your decisions. Take these articles as a structured way to describe my experience, nothing more.

- Building and maturing an open source project takes time, effort, money, and commitment. This iteration requires a strategic decision from the company in order to succeed, even if you start small, as I recommend. In my experience, the pressure on showing ROI grows significantly after the incubation stage. Be ready for it.

- Use consistent reporting formats, aligning metrics, KPIs and reports for both cycles — downstream and upstream — as much as possible (I pointed out cases in which you should not). Think about your ecosystem as stakeholders and shareholders. Involve them in your reporting strategy. When the time for decision makers to evaluate the investment comes, those in your company’s ecosystem participating downstream might become your best allies.

Summary

This first iteration of the virtuous open source cycle is a natural evolution of the basic model. It adds a corporate-led downstream project that acts as a bridge between your internal teams and the open community. The main goal is to reduce friction when direct contribution to upstream projects becomes hard, while ensuring value keeps flowing in both directions. This approach works best for organizations facing complex integration needs, multiple dependencies, or a need for a safe, shared space where partners can collaborate and share costs.

Next, study your needs and upstream targets. Apply the simplest model to master it. Identify gaps and go for this first iteration if it suits you. Once you have set up the downstream project, it will be the time to apply this model.

Start small and learn first, before working on optimizations and scaling up flow. This learning phase teaches you how to invest wisely. Remember:

- This first iteration will require a greater activation energy compared to the simple one.

- The downstream project should become a learning lab which will, among other benefits, help you proving to decision-makers the return in value of investing in the open source commons.

- Adapt metrics and KPIs to each environment only when truly required. Try to keep metrics and KPIs, but especially reporting, consistent across the model.

Think of this iteration as a foundation step in your open source journey, where you are building infrastructure for open collaboration with the open source community and your company’s ecosystem in an environment that, although more complex and expensive, it gives your organization the change to adapt internally to how open source works at a more digestible pace.

8. Next steps

In my first article, I explained the basic model. We showed how activation energy starts the cycle and we described how value exchange keeps it running. In my second article, I moved from theory to practice, showing how to plan your implementation while maintaining momentum.

In this article, we addressed the limitations of the simplest model and evolved it to suit a corporate environment facing high friction. We added complexity by creating a downstream open source project, described its purpose, and provided practical advice for its implementation.

Remember that there are other articles corresponding to this Open Source Value Flow Model series:

- Article one: The Virtuous Open Source Cycle: Model Description

- Article two: From Theory to Practice: Leveraging the Virtuous Open Source Cycle for Long-Term Success

- Article four: Value Types: Reputation and Influence

The text of this article has been polished using different AI services. The Mind Map has been created using NotebooLM

3 thoughts on “Part 3: Evolving the Model by adding a company-driven open source project”