Doing Open Source the right way: freeing up people and capital to focus on what truly matters

I worked as a manager in operating system projects for many years. When I moved into the automotive sector as a consultant, I spent many hours explaining to very smart managers and executives how open source works, why automotive companies should invest in and directly participate in open source projects, why they should build InnerSource projects with their suppliers, and why they should turn their existing relations from supplier-OEM type to partnership ones, building more sustainable ecosystems.

Most of the executives I spoke with were familiar with the lower TCO associated with “this kind of software,” as some used to call it. A smaller group understood the basics of software licenses, usually through their experience with patents or regulatory compliance. This often lead them to see the GPL as “bad for business”, for instance.

As you can imagine, there were misconceptions to correct, some new concepts to explain, and very little time to get their attention. I needed to show why investing in and participating in open source projects — in the open — is positive for their business.

This blog post describes a line of thinking I have used in the past to “sell” the idea of investing in open source and InnerSource to automotive OEM senior managers and executives. These companies already invest heavily in software, yet they struggle to build several lines of in-vehicle platforms and application ecosystems in a sustainable way.

I have used these ideas many times, in different forms. What you will read here is not new, and the way I present it is not new either. But since I reviewed this material again a couple of months ago, I decided to write it down so I could share one clear reference for others.

The introduction

The title of the talk I describe here is something like: “Why doing open source is good for <target company name> business?”

I usually start with a slide full of logos from well-known companies that lead their markets and actively do open source. I choose logos that the audience can easily relate to, so the impact is stronger. The idea that “the most innovative software companies do it” is useful only to catch their attention at the beginning, not as a core argument.

I explain that these companies have understood something strategic that the target company has not. They have access to the same information, the same reports, and the same market data. This is not about investing more money, collecting more information, or trying harder. It is about focusing on different things and understanding how open source — and co-creation — can work for a large automotive company.

Then I ask the key question: What have these leading companies learned that the audience has not yet?

I tell them that I will answer this question by explaining three simple concepts and by walking them through a set of drawings that represent a journey — a different way of thinking.

I summarise the ultimate goal: to help the company focus more effort and capital on what matters (differentiation), using the same amount of resources, while managing even more software.

Or, as I prefer to say: to increase the executives’ ability to steer the company and create a bigger impact on the business.

I clarify that participating in open source — in the open — is a necessary step to reach this goal, but not the only one. The further the company goes on this journey, the greater its ability to redirect resources toward what truly matters.

The concepts

At this point, I explain to the audience what I will cover: two concepts and several drawings that describe the journey.

I introduce three useful ideas:

- Differentiation vs. commodity software

- The Pareto principle

- Co-creation: collaboration the open source way (open source and InnerSource)

I no longer define the third concept here. Over time, I learned that it is easier for the audience if I explain co-creation later, exactly when I need it.

The slides below are examples from an early presentation on this topic. I have refined them many times since then, but the approach remains the same: simple, direct, and solid enough to build a foundation.

The journey

Once these concepts are explained, although I prefer to develop the third one later, the rest of the presentation is guide through drawings. The amount of time I have to deliver the presentation reflects from now on. The more time I have, the more steps I add to the journey, so the more drawings I show. But, as usual, the conversation is the priority.

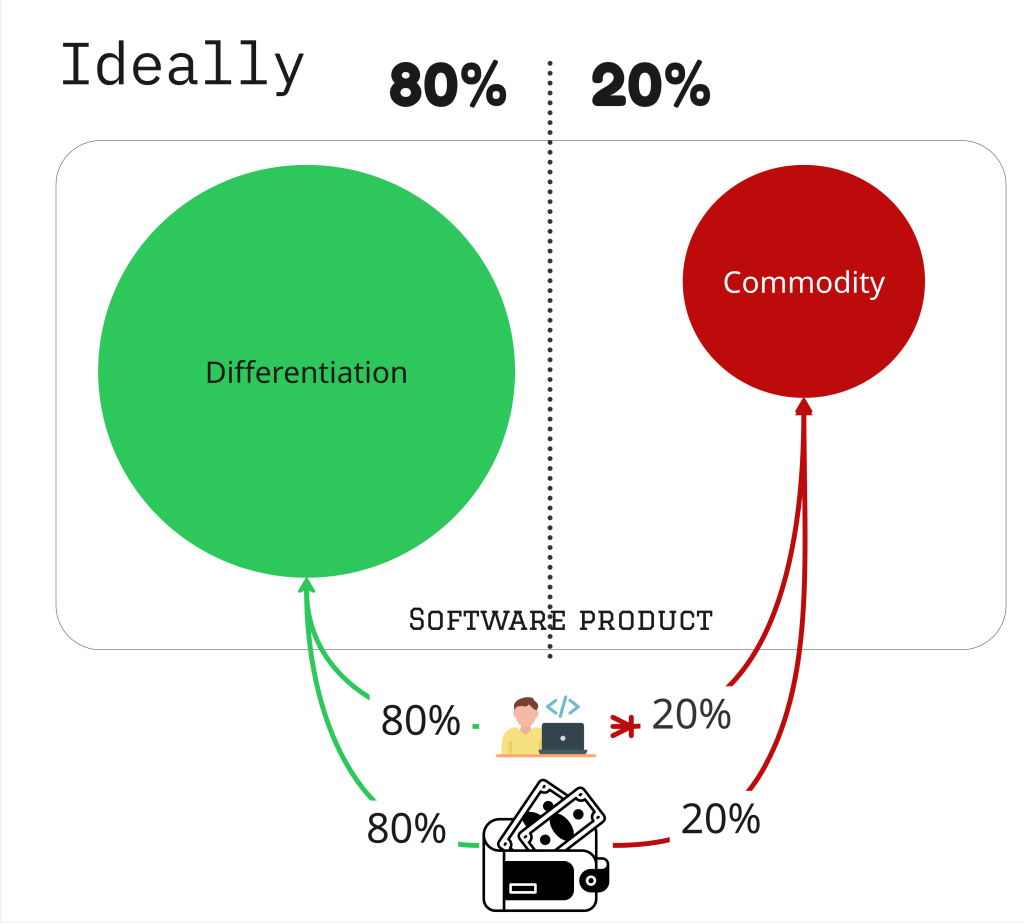

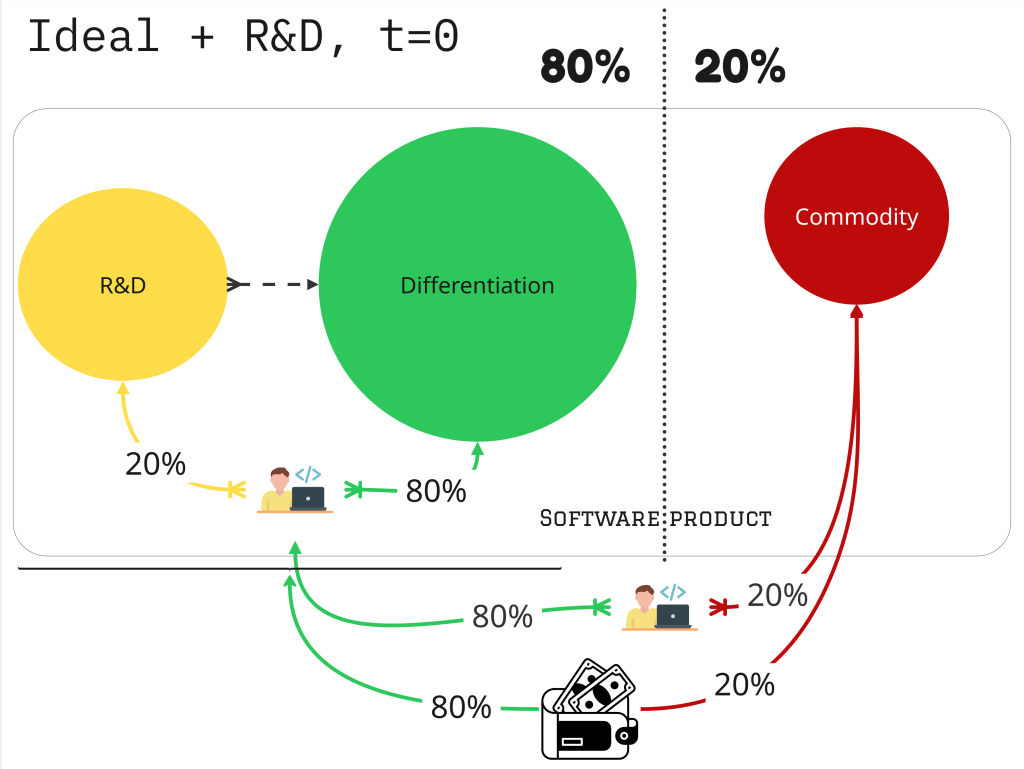

Graph 1: where every executive wants to be: maximum focus on differentiation

I start by describing the ideal situation, the one every automotive executive would like to see: most of their software investment goes into features that create differentiation.

I explain how expensive it is to understand and maintain software that their developers did not create. Then I explain how quickly differentiation turns into commodity because of the digital nature of software.

I close this first drawing by explaining how hard and costly it is to outsource or deprecate internally developed commodity software. They are usually the only ones who fully understand it. The way the software was created shapes the software itself (Conway’s Law), and in-house commodity software is often tailored to very specific internal needs from the beginning.

Graph 2: Adding R&D changes the picture

Here I focus on the importance of investing in software R&D. Historically, automotive companies did not invest much in R&D for in-vehicle software. They preferred to buy solutions instead of creating them, unlike in other critical areas of their business.

I acknowledge that this has changed. Today, the strategic value of software is widely accepted across the industry.

At this point, I adapt the message to the maturity level of the company. Speaking to executives building their own in-vehicle platform is very different from speaking to a company that relies on a third-party solution like Android Automotive. The context shapes the argument.

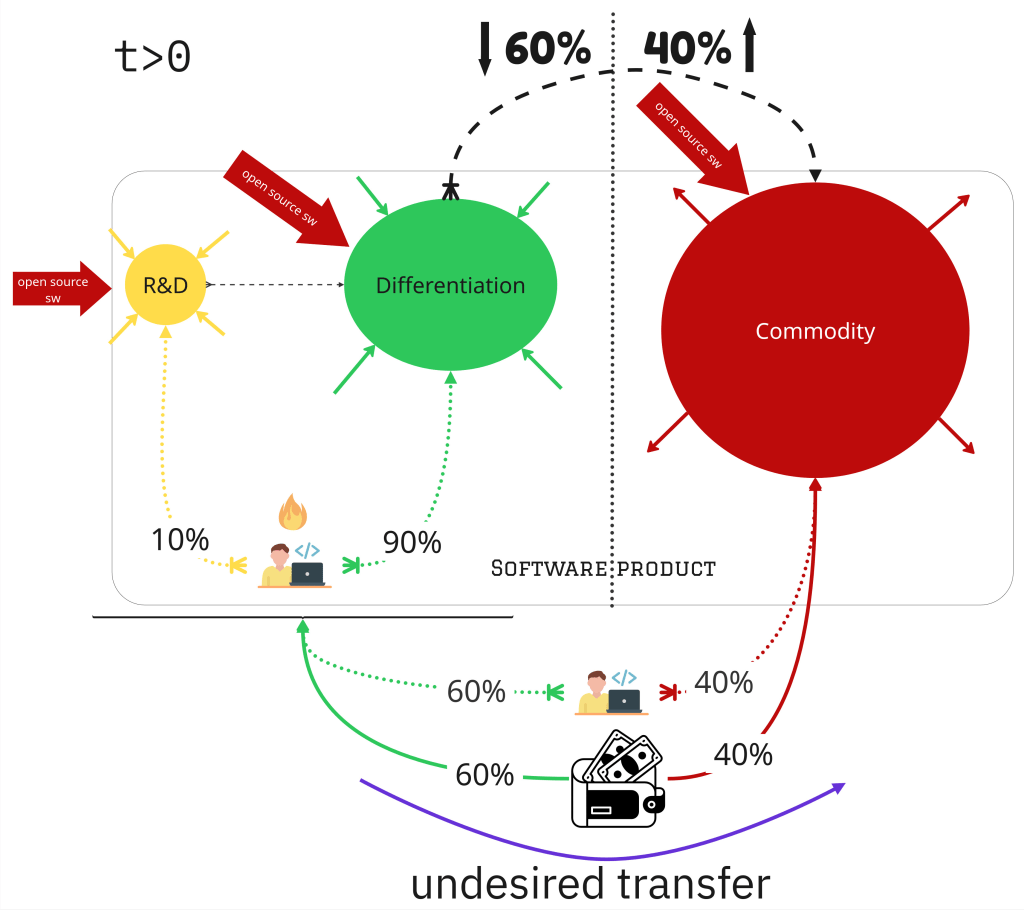

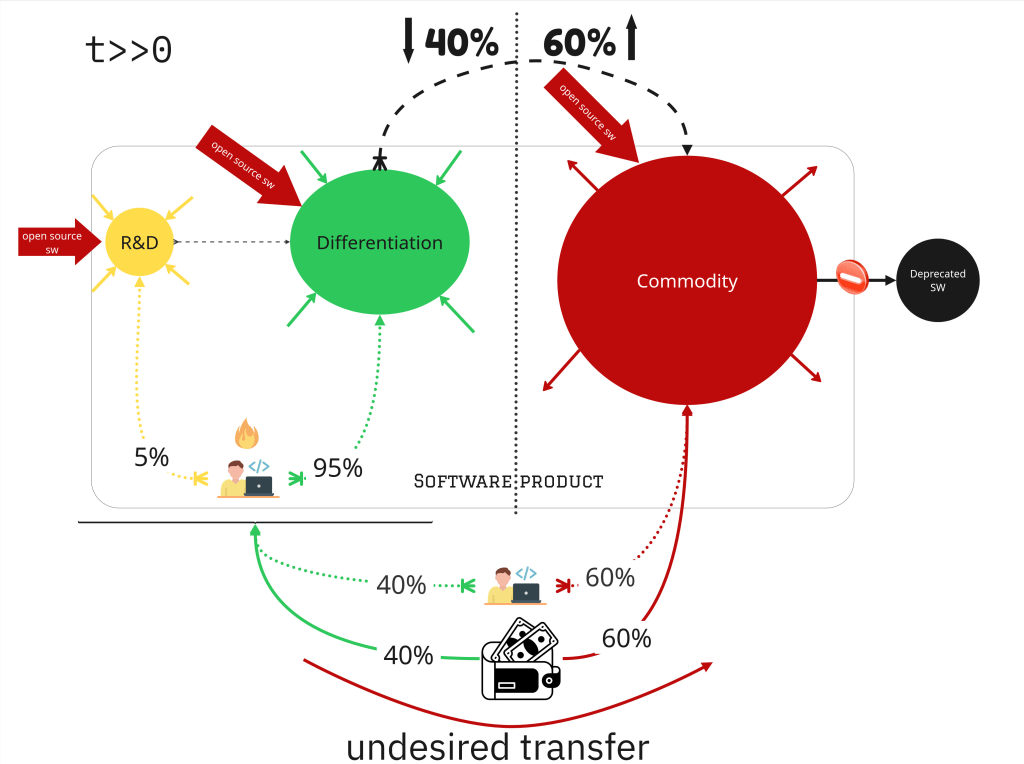

Graphs 3 and 4: current reality in automotive

Here I highlight the main challenges automotive companies face today, especially around resource and capital allocation:

- A significant part of the software that should provide differentiation is still bought, not developed internally. This adds integration and maintenance costs and shortens the lifespan of differentiation in the market.

- Open source software is consumed everywhere and in large quantities, but with little or no active involvement in its development.

- Over time, differentiation turns into commodity. The amount and complexity of commodity software grow, and maintaining it consumes more resources and capital. This reduces the capacity to focus on new differentiation. The problem is amplified by the heavy use of open source and purchased proprietary software — often without enough internal knowledge about them.

- The pressure to keep delivering new differentiation forces R&D teams to prioritize productization and shipping. This reduces their ability to innovate for the next product cycle.

Companies usually respond to these challenges with two common strategies:

- Outsourcing the maintenance of commodity software — either by replacing it with a purchased solution or by transferring knowledge to a service provider who maintains it at a lower cost. This frees internal resources but requires capital and has limits, especially when products must be maintained for many years.

- Starting a new generation from scratch, instead of evolving the current one. This absorbs most resources, leaving older generations understaffed and with limited upgrade paths.

If you do not “hit the nail” here, you lose the audience. Everything that follows depends on them seeing their own struggles reflected in these points. This is where prior knowledge of the company — or good internal context — makes a major difference.

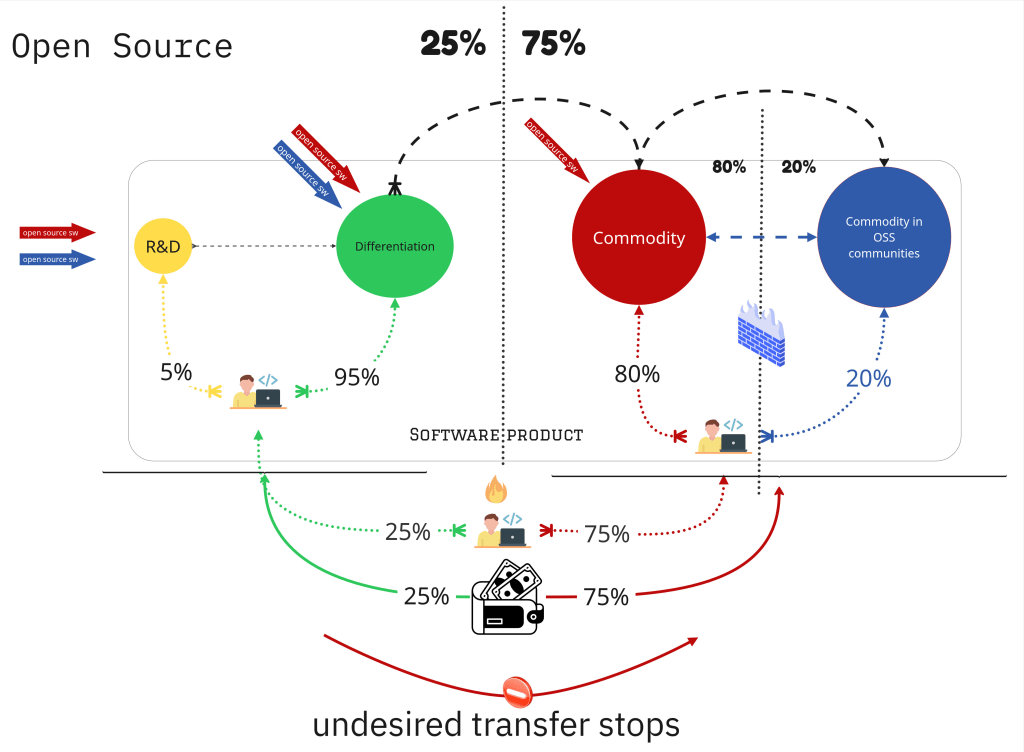

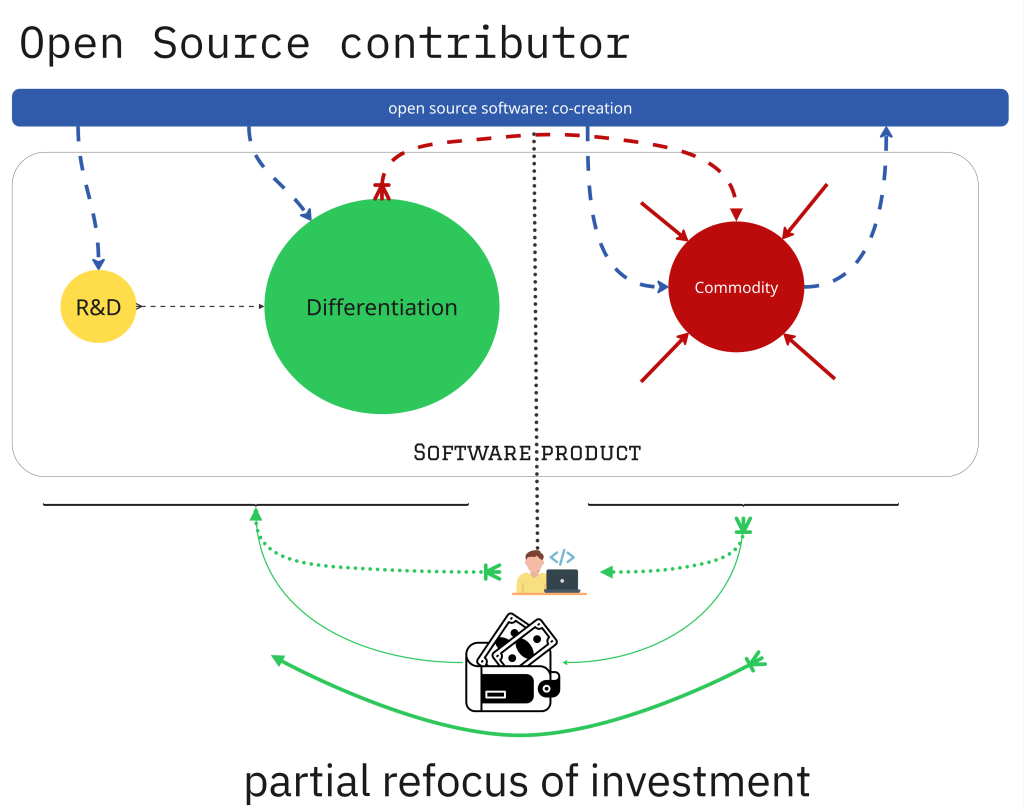

Graph 5 and 6: co-creation: a smarter way to outsource commodity software

Here I explain the concept of co-creation. By contributing even a small but meaningful percentage of the code, a company gains direct or indirect knowledge of a much larger part of the codebase — the open source community’s work.

Through co-creation, they:

- understand how the entire software is built,

- build relationships with the other contributors,

- influence the project roadmap, and

- anticipate and reduce future risks.

All of this is essential for reducing the cost of consuming the software over its full life cycle.

Co-creation works in two environments: InnerSource and open source communities. I briefly explain both.

From a “solution” point of view, this is the hardest idea to sell. Automotive executives understand traditional collaboration models — joint ventures, supplier–integrator, manufacturer–seller, aftermarket services — but not co-creation in the open source sense.

I take extra time to explain that co-creation is a different kind of collaboration, one that fits software particularly well. Software behaves more like a liability than a traditional component. However, when speaking to automotive executives, I am careful with the word liability. They know far more about liability than we do. I never assume the concept is understood; I reinforce it whenever I can.

I highlight that learning co-creation is not only an operational skill. It also requires understanding the economics of open source. Mastering this concept is essential. It is the foundation that makes the rest of the solution work.

Then I connect back to the introduction: the companies I showed at the beginning mastered this concept. Their strategies are a consequence of that mastery.

I also challenge the way automotive companies think about outsourcing. Three alternative strategies appear here:

- Turning suppliers into co-creators through InnerSource

- Outsourcing “the open source way” — paying companies to co-create the needed (commodity) software in open source projects

- Contributing in the open with your own staff — because your developers still build only specific parts of a much larger code-base

I insist that companies already have enough internal knowledge to start this journey. They simply need to empower the right people to lead it.

From a strategic point of view—supporting the “drivers” of the change—I usually advise them to:

- “hire a few experts, and”

- “add two or three profiles who support the open source team from a business and product perspective.”

The goal is to reduce the ramp-up time and reach a stable “cruising speed” sooner.

I still cannot decide whether to place a dedicated slide explaining co-creation before or after this drawing. Both options work, depending on the flow.

I remind them: you are not describing a slide; you are describing a journey. Focus on the idea that co-creation enables a different way to allocate resources — one that frees more capacity for differentiation.

Graph 7: from commodity co-creation back to R&D

This is usually the most creative part of the presentation. I even had an “aha!” moment here during a talk — one of those moments when the idea suddenly becomes very clear.

Until now, the focus has been on managing resources for commodity software. With this drawing, I connect co-creation in commodity software with the company’s R&D efforts.

When a company co-creates software that is commodity for them, that same software may be innovation for others — and sometimes, if done well, it can even become innovation for the company itself. This is especially true for software that others consider commodity but that can support your R&D needs.

This creates a cycle:

- you invest resources in co-creation,

- you multiply the value of that investment through community collaboration, and

- you bring that value back into the company.

Resource allocation becomes more flexible while co-creation increases the return on investment (ROI) of both, commodity and R&D software. I emphasize this idea whenever I can.

By co-creating “the open source way,” you also make maintenance easier. The knowledge transfer that happens inside the community naturally reduces effort, lowers external dependency, and gives you more control.

The result is simple:

you free up more capacity for differentiation — and you reduce the amount of software you must maintain by yourself.

The rest of the presentation builds on this cycle. Even if the audience gets lost in some details, they usually leave with a clear message:

“there is a cycle the company must build — one that makes software management more scalable and shifts resources from commodity to differentiation, increasing the transfer of R&D into products.”

Be ready to questions related with the how: how is resource allocation more flexible?… and so on. Ask them to allow you to continue and then formulate the question again if it is not answered.

Graph 8: adding flexibility in resource allocation through co-creation

Building on the concept of co-creation, this is where I explain why it is smarter to consume software you co-create than software you do not contribute to.

Thanks to the “multiplication effect” of collaboration in co-creation environments, knowledge spreads faster, and maintenance becomes easier and cheaper.

At this point, I introduce a key idea:

“the differentiation software you build internally should rely on — and be closely connected to — the software you co-create externally and internally (open source and InnerSource).”

This approach maximises:

- the value that flows from R&D into differentiation, and

- the amount of commodity software you can manage through shared development and maintenance — even before it becomes commodity for your company.

I highlight the role OEMs play in shaping their ecosystems. This influence is powerful, but when it comes to software, it is often underused. Many OEMs still manage software relationships as if they were physical components. That approach creates friction and increases cost.

Co-creation, on the other hand, aligns much better with how software is built, maintained, and evolved.

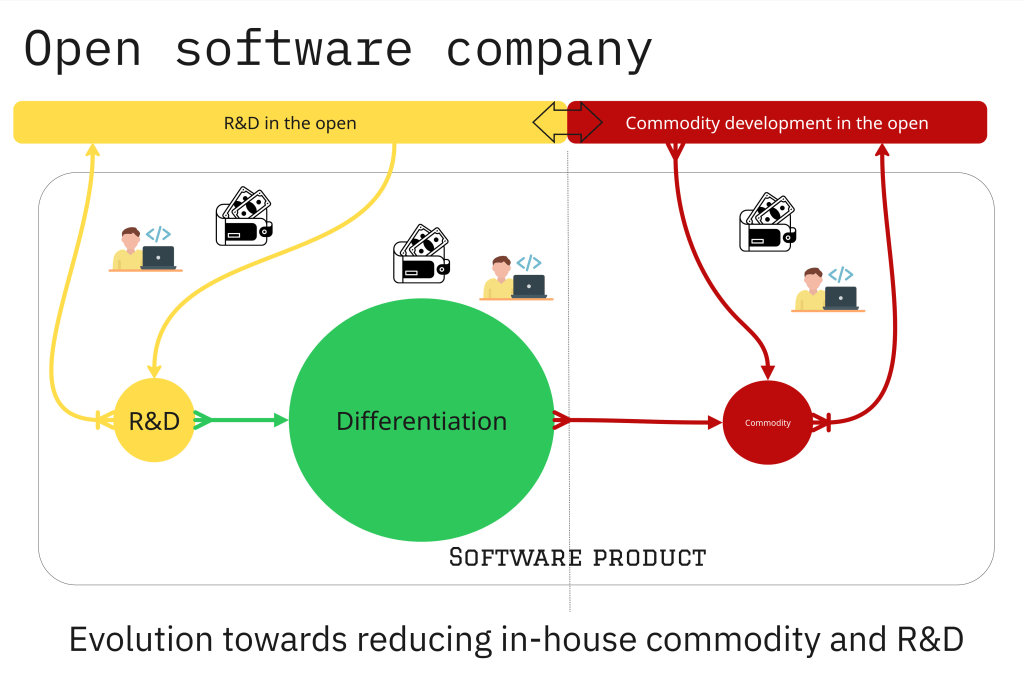

Graph: 9: becoming an open source company

This is when you explain that, taking this idea further and scaling it up, is what justifies the behavior of leaders in certain markets.

They do not just consume open source and contribute to the open source projects where that commodity (for them) software is created. They also open-source technologies and tools early – some even at the R&D stage. On top of that, they have partly adapted the production of their software internally to how software is co-created internally, with their now partners (instead of suppliers), and externally, as part of the ecosystem of open source projects. This adaptation reduces friction and makes consuming and sharing co-created software cheaper.

I have never had the chance to go further than this slide. Once, I got a question about what a specific company did, which is a well-known, reputed open source company. I mentioned that they went two steps further in this journey, where they have built a business model in which the differentiation software is not essential anymore, so they can also co-create most of it in the open, as well as most of the commodity and R&D software.

Conclusion

No matter how many drawings I show, my conclusions do not change.

Why should <target company’s name> do open source?

Because by doing open source, the company will be able to — with the same amount of capital and people (I interchange “people”, “resources” and “capacity”, as you have probably noticed) — achieve the following:

- Increase its capacity to allocate resources to differentiation.

- Manage more software overall…

- …and less commodity software by themselves (people or capital).

- Increase the amount of R&D software they can digest and turn into differentiation.

- Turn the nature of their current relations — from suppliers and outsourcing service companies — into partners they co-create with, internally and externally.

- Open themselves to a new type of fruitful, long-term relation with additional companies they co-create and maintain R&D and commodity software with, thereby increasing their knowledge transfer with a bigger ecosystem.

So…

…achieving faster time-to-market while increasing innovation throughout this journey depends, to a great extent, on how well this strategy is implemented.

Finally…

In software, there is no sustainable alternative to co-creation in order to scale up the amount of software they manage while keeping a high innovation rate.

Final Notes

I understand that there might be more direct and simpler ways of answering the question. I simply describe here one that has worked for me in the past with this specific audience, considering that any successful argument depends not only on the target audience and how well it is delivered, but also on the stage of the life cycle and the open source journey the company is in at the moment of the discussion. If the context is different, these arguments might not be effective, even if they are properly delivered.

About the drawings, these are just drafts. Tailor them for your purpose and target company/audience. I recommend you to keep a consistent color scheme and, when possible, use one compatible with the target company’s branding. It will be easier to digest by your audience. The vocabulary is relevant too. In the same line, I recommend you to use one they feel comfortable with.

In any case, I hope you find this exercise useful. Please let me know. Mastering these kinds of presentations is essential for my job, and I still have a lot to learn.